What is the skillset of an expert functional programmer?

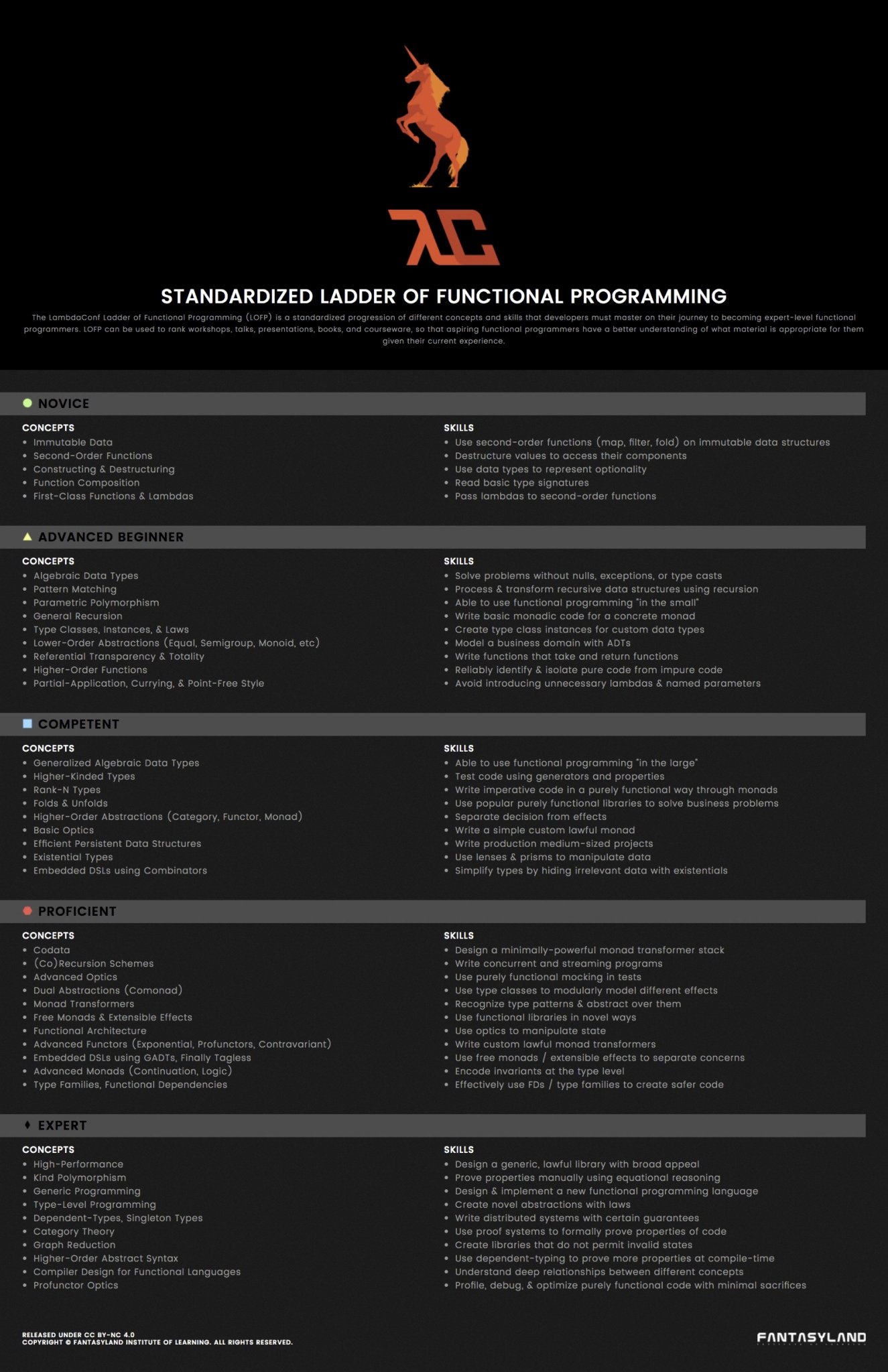

According to the “Standardized Ladder of Functional Programming”, a graphic I found on Reddit, there is a standardized progression of different concepts and skills that a developer must master to be considered an expert in functional programming:

Whether or not this is true is debatable at best; many people criticized this graphic as being non-realistic. However, the ladder does pick interesting topics and puts them in a relatively increasing order of complexity, so I thought it would be fun to do a series on reviewing the concepts and skills for each level. I won’t do a deep dive because topics are easily found with a quick google search, but I will give a brief review on each concept.

This is part 1 of the series, so I will be covering the “Novice” portion of the graphic.

Immutable Data

In general, immutable data is data that cannot be changed. Once data is bound to a variable, the data cannot be modified.

For example, variables in Python are mutable, so once we assign a value to a variable, we can mutate it:

# immutable_data.py

if __name__ == '__main__':

x = [1, 2, 3]

print(x) # prints "[1, 2, 3]"

x.reverse()

print(x) # prints "[3, 2, 1]"As we can see, the variable x has been modified.

In Haskell, variables are immutable. In the following example, reversing the list does NOT modify the variable x:

-- immutable_data.hs

main = do

let x = [1, 2, 3]

putStrLn $ show x -- prints "[1, 2, 3]"

putStrLn $ show $ reverse x -- prints "[3, 2, 1]"

putStrLn $ show x -- prints "[1, 2, 3]"

There are a few benefits of making data immutable:

- Variables can’t change values, consequently removing the mental task of tracking a variable’s state.

- Variables are inherently thread-safe since they cannot be modified by various threads.

Both of these benefits contribute to code that is easier to read and comprehend.

Conversely, a negative aspect of immutability is that it’s more memory-inefficient; if data does need to be modified, a clone of the object has to be created in memory (with modifications applied) as opposed to having the same object being modified.

In languages like Rust and OCaml, variables are immutable by default and must be explicitly marked to be made mutable. This allows those languages to take advantage of both immutable and mutable data types.

For a more concrete example, a program may need to manipulate a large array of data. It is not ideal to make a new copy of the array every time it is modified. Therefore, marking the array as mutable can take advantage of improved speed and memory efficiency, while other data in the program utilize the advantages of immutability:

// immutable_data.rs

fn main() {

let mut list = [1, 2, 3];

println!("{:?}", list); // prints "[1, 2, 3]"

for number in &mut list {

*number += 1;

}

println!("{:?}", list); // prints "[2, 3, 4]"

}If were were to not include the mut and &mut keywords:

// immutable_data_fail.rs

fn main() {

let list = [1, 2, 3];

println!("{:?}", list);

for number in &list {

*number += 1;

}

println!("{:?}", list);

}The program would fail during compilation with an error being raised due to not being able to modify number because it is "behind a & reference`, which are immutable by default:

$ rustc immutable_data_fail.rs

error[E0594]: cannot assign to `*number` which is behind a `&` reference

--> immutable_data_fail.rs:8:9

|

7 | for number in &list {

| ----- help: consider changing this to be a mutable reference: `&mut list`

8 | *number += 1;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^ `number` is a `&` reference, so the data it refers to cannot be written

error: aborting due to previous errorSecond-Order Functions

A second-order function is a function that either:

- takes another function as input

- returns a function as its result

In general, a second-order function is categorized as a higher-order function. A function that is not a higher-order function is a first-order function and does not take a function as input or return a function.

A common pattern in software are list transformations, where a function is applied to each element in a list. To illustrate, this is a list transformation in Python using an imperative programming approach:

# second_order_functions.py

def add_one(number):

return number + 1

if __name__ == '__main__':

list = [1, 2, 3]

new_list = []

for number in list:

new_number = add_one(number)

new_list.append(new_number)

print(number) # prints "[1, 2, 3]"

print(new_number) # prints "[2, 3, 4]"However, in a functional language like Haskell, a second-order function such as map, which has parameters function and list, can be used to directly apply a function to each element in the list:

-- second_order_functions.hs

add_one :: Int -> Int

add_one number = number + 1

main = do

let list = [1, 2, 3]

let new_list = map add_one list

putStrLn $ show list

putStrLn $ show new_list

Where map literally maps (from a mathematical perspective) one list to another via the function. This allows a programmer to think in terms of list transformations and also reduce the multiline for-loop structure into a one line expression. This arguably reduces complexity during development, leading to improved comprehensibility of the code.

Constructing and Destructuring

Constructing is a technique for building objects while destructuring is technique for extracting data from those objects.

The following Haskell example uses record syntax, where the data type Person is created with the fields firstName, lastName, and age. This autogenerates functions firstName, lastName, and age, which can be used to access the respective data from a Person object:

-- constructing_and_destructuring_1.hs

data Person = Person

{ firstName :: String

, lastName :: String

, age :: Int

}

main = do

let person = Person "James" "Kurt" 25

putStrLn $ firstName person -- prints "James"

putStrLn $ lastName person -- prints "Kurt"

putStrLn $ show $ age person -- prints "25"The same concepts apply to lists and tuples. There are various ways to construct and destructure these types:

-- constructing_and_destructuring_2.hs

main = do

let list1 = 1 : 2 : 3 : []

let list2 = [1..10]

putStrLn $ show $ head list1 -- prints "1"

putStrLn $ show $ tail list1 -- prints "[2, 3]"

let tuple = (1, 2)

putStrLn $ show $ fst tuple -- prints "1"

putStrLn $ show $ snd tuple -- prints "2"

Here is a similar example in Rust that uses different destructuring tactics than Haskell:

// constructing_and_destructuring.rs

struct Person {

first_name: String,

last_name: String,

age: u8

}

fn main() {

let person = Person {

first_name: "James".to_string(),

last_name: "Kurt".to_string(),

age: 25

};

println!("{:?}", person.first_name); // prints "James"

println!("{:?}", person.last_name); // prints "Kurt"

println!("{:?}", person.age); // prints "25"

match person {

Person {

first_name: a,

last_name: b,

age: c

} => println!("{} {} {}", a, b, c) // prints "James Kurt 25"

}

let tuple = (1, 2);

println!("{:?}", tuple.0); // prints "1"

println!("{:?}", tuple.1); // prints "2"

let (first, second) = tuple;

println!("{:?}", first); // prints "1"

println!("{:?}", second); // prints "2"

}Ultimately, constructing and destructuring is about creating objects that store data and techniques for extracting that data into other usable forms.

Function Composition

A function composition is the act of composing two or more functions. From a mathematical perspective, the common syntax for the functional composition of f(x) and g(x) is f(g(x)) and f . g (x). From an information flow perspective, the data x is inputted to function g and the output is inputted to function f. This allows various chaining of operations.

The following Haskell code demonstrates this concept using the . operator for function composition:

-- function_composition.hs

add_one :: Int -> Int

add_one x = x + 1

make_negative :: Int -> Int

make_negative x = -x

main = do

let f1 = make_negative . add_one

putStrLn $ show $ f1 0 -- prints "-1"

let f2 = make_negative . add_one . add_one

putStrLn $ show $ f2 0 -- prints "-2"

It is important to note from the example that operations of the function composition execute from right to left. This is analogous to the inner function being evaluated before the outer function.

The ability to chain functions together leads to easier development of pipeline design patterns. Moreover, it promotes modularity and code-reusability because functions are easily interchangeable.

First-Class Functions & Lambdas

First Class Functions

A language supports first-class functions if it allows functions: 1. to be passed as arguments to other functions 2. to be returned as values from other functions 3. to be assigned to variables

This is closely related to higher-order functions and function composition, because a language must support first-class functions if it intends to support either of these concepts.

According to wikipedia, the most popular languages provide some degree of first-class functions.

Haskell supports first-class functions and can demonstrate all 3 requirements:

-- first_class_function.hs

add_one :: Int -> Int

add_one x = x + 1

do_nothing :: Int -> Int

do_nothing x = x

execute_if_even :: (Int -> Int) -> Int -> Int

execute_if_even func x = if even x then func x else do_nothing x

main = do

let list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

let add_one_if_even = execute_if_even add_one

let new_list = filter even list

putStrLn $ show $ new_list -- prints "[1, 3, 3, 5]"We can see that:

- The function

add_one_if_evenis an argument to the functionmap. - The function

execute_if_evenreturns a function. - The function returned by

execute_if_even add_oneis stored in the variableadd_one_if_even.

Furthermore, here is a similar example in Python that exhibits the 3 requirements:

# first_class_function.py

def add_one(x):

return x + 1

def do_nothing(x):

return x

def execute_if_even(func, x):

if x % 2 == 0:

return func

else:

return do_nothing

if __name__ == '__main__':

list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

new_list = []

for number in list:

function = execute_if_even(add_one, number)

new_list.append(function(number))

print(new_list) # prints "[1, 3, 3, 5]"Lambdas

A lambda function is also known as an anonymous function because they don’t require a name. In Haskell, for example:

\x -> x + 1The syntax for is as follows:

- Everything between the “

\” and “->” will be parameters - The function body is to the right of “

->”

There can be multiple parameters:

\x y z -> x + y + zArguments can be applied as such:

> (\x y z -> x + y + z) 1 2 3

6Lambdas allow closures and currying to be developed, which will be discussed in later blog posts.

A named function can be used anywhere a lambda function is used, however, sometimes it’s convenient to use a lambda function, especially when the function is small. Here is our map example again, except using an anonymous function as opposed to defining an incrementing function:

-- anonymous.hs

main = do

let list = [1, 2, 3]

let new_list = map (\x -> x + 1) list

putStrLn $ show list -- prints "[1, 2, 3]"

putStrLn $ show new_list -- prints "[2, 3, 4]"